In September 1862 Lincoln’s attention was diverted from the day to day operations of the Civil War to an uprising among the Sioux Indians of Minnesota.

In 1851 the U.S. government signed two treaties with the Sioux for large portions of the Minnesota Territory in exchange for compensation in the form of annuity cash payments and trade goods. They were allowed to keep a reservation along the upper Minnesota River. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was the institution responsible for managing the terms of the treaties. Over the years the organization grew corrupt and resources were not directed to the Sioux people, instead they were used to bribe traders and Indian agents but most of the funds went directly to Washington politicians.

In 1858 when Minnesota entered the Union, Chief Little Crow visited Washington to ensure the treaties were being enforced. Instead the government repossessed half of their territory and opened it to new white settlers. Diminished annuity payments for land they gave up had left them unable to provide for basic necessities. In August 1862 some Sioux men broke into a farm to steal eggs and killed five white farmers. Suddenly the violence spread through the region and more than 350 settlers were killed.

President Lincoln assigned Gen. John Pope whose task was to end the uprising. On September 2, in the battle of Wood Lake the Sioux were defeated and 303 were ordered to be executed. Episcopal bishop, Henry Whipple, advocated for the Sioux in the White House asking Lincoln to re-examine every case. Only 38 of the accused were proved to have participated in the uprising.

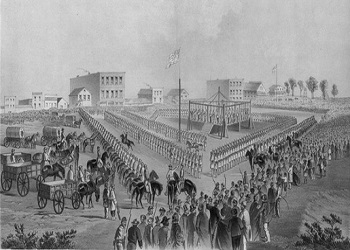

On December 26, 38 Sioux men were executed in the largest public execution in American history. Minnesota’s residents were not happy that the execution list had been reduced from 303 to 38. Protest did not die down until reasonable compensation for the loss of settlers’ property was offered. The president’s action was not a popular one in an election year. He responded “I could not hang men for votes”. Lincoln did not let the power of law be overpowered by revenge and took time to review each case during a critical time in the Civil War.